The Investor's Case for Bitcoin

Assessing the prospect of buying Bitcoin through a traditional investing paradigm can often lead to confusion or dismissal. This approach commonly brings people to preliminary objections which prevent them from understanding the case for Bitcoin on a deeper and more holistic level. This tendency is not confined to the average person - the ECB’s most recent blog exemplifies it:

“Bitcoin is still not suitable as an investment. It does not generate any cash flow (unlike real estate) or dividends (stocks), cannot be used productively (commodities), and offers no social benefit (gold jewellery) or subjective appreciation based on outstanding abilities (works of art).”

This article aims to explain why this form of thinking has become so pervasive, and ultimately why it is wrong. A comprehensive explanation of the case for Bitcoin is best achieved through a monetary lens; however, this article will take a somewhat different approach by emphasising the shortcomings of investing in today’s world and explaining why understanding Bitcoin is an essential component of any modern investor’s (or indeed saver’s) worldview.

What is Investing?

The Collins English Dictionary states:

“If you invest in something, or if you invest a sum of money, you use your money in a way that you hope will increase its value, for example by paying it into a bank, or buying shares or property.”

Obviously one can invest many things other than money, including time and effort. The expected value of investing time and effort is quite personal, whereas the investment of money may appear to be more measurable or objective: the general aim is to get more out than you put in. Notwithstanding this, investing money is also highly subjective in many ways. People who do so are not just concerned with how much money they will make, but also how much risk or uncertainty an investment carries, over what period of time they can expect any return, and the opportunity costs of present expenditures that must be foregone.

In the context of investing money, we can simplify the concept by saying that it describes a process in which people are willing to take some degree of risk in an attempt to increase the purchasing power of their money over time, unique to their particular circumstances and tolerances. This can be achieved either through an expected appreciation of the value of the thing itself or some form of income derived from it, or both.

Investing vs. Saving

We need no dictionary to agree that saving merely entails deferring consumption from the present to the future so that we retain the purchasing power we have already accrued. We intuitively think of saving as being generally risk free, while also understanding that it is unlikely that the purchasing power we have obtained will actively increase.

We can summarise the difference between investing and saving by saying that when we invest, we ‘put our money to work for us’, entailing some degree of risk and reward, whereas when we save, we are merely leaving our money idle to use in the future.

The distinction between investing and saving has become increasingly unclear, which in our view largely explains the malaise in thinking on this topic generally. Let us imagine, as a thought experiment for the sake of mental clarity, that money generally retains its value over time because it has a fixed supply. In such a world, the distinction between these concepts would be easily drawn.

Investing in a Closed System

Those who wish to take no risk and save their purchasing power would do so by simply doing nothing. Nothing ventured, nothing gained; and importantly - nothing lost. Whether a person saves in a fully reserved bank with legal claim over their money or by stuffing cash under their mattress is immaterial. Their respective ownership share of society’s value accounting system remains unchanged over time. The only way for money to lose or gain value against real goods and services is for the economy to become less or more productive, but the proportion of their claim within it doesn’t change.1

In such a closed system, anything beyond holding your money logically enters the realm of investment. On the more conservative end of this wide spectrum a person might consensually deposit their money with a bank that is not fully reserved for a small rate of interest. This would mean that the bank is likely taking on risk with your money to finance something or someone (a borrower) with an expected positive return - you are now on one contractual end of a multi-party investment. There is a risk that the bank’s risk practices are deficient or that the borrower won’t be able to repay, and you might lose some or all of your money. On the other end of the spectrum, you might decide to buy shares of a small start up company with a bold vision promising a high potential return. In this case, you are also an investor, albeit a more aggressive one.

In this world, we all play a transparent and zero sum game with our economic energy. For every investor’s Euro that becomes two, another’s two becomes one. The savers maintain their position, moving neither forward nor backwards. Although this might seem alien to us given the way the world currently works and in which most investments are expected to go up over time, it merely describes a world in which risk and reward function efficiently, and in which capital is best allocated.2 This is also a world in which what is known as ‘value investing’ is of primary importance. When we use that term, you can think of a Warren Buffett style investor who analyses a company’s fundamentals to determine whether it is overvalued or under, and allocates their money accordingly. This is seen by many as the stereotypical form of investing.

This is the world in which many people think and act as if they operate in. This belief, whether conscious or unconscious, is mistaken. The fundamental cognitive error is acting as if the unit of measurement itself, the money, is fundamentally fixed and risk free, and that it constitutes a ground level of reality from which other things can be accurately gauged - a closed system. With this erroneous worldview, investing appears to be a relatively straightforward concept. If you make more money than you lose, you have succeeded.3

Blurred Lines in the Real World

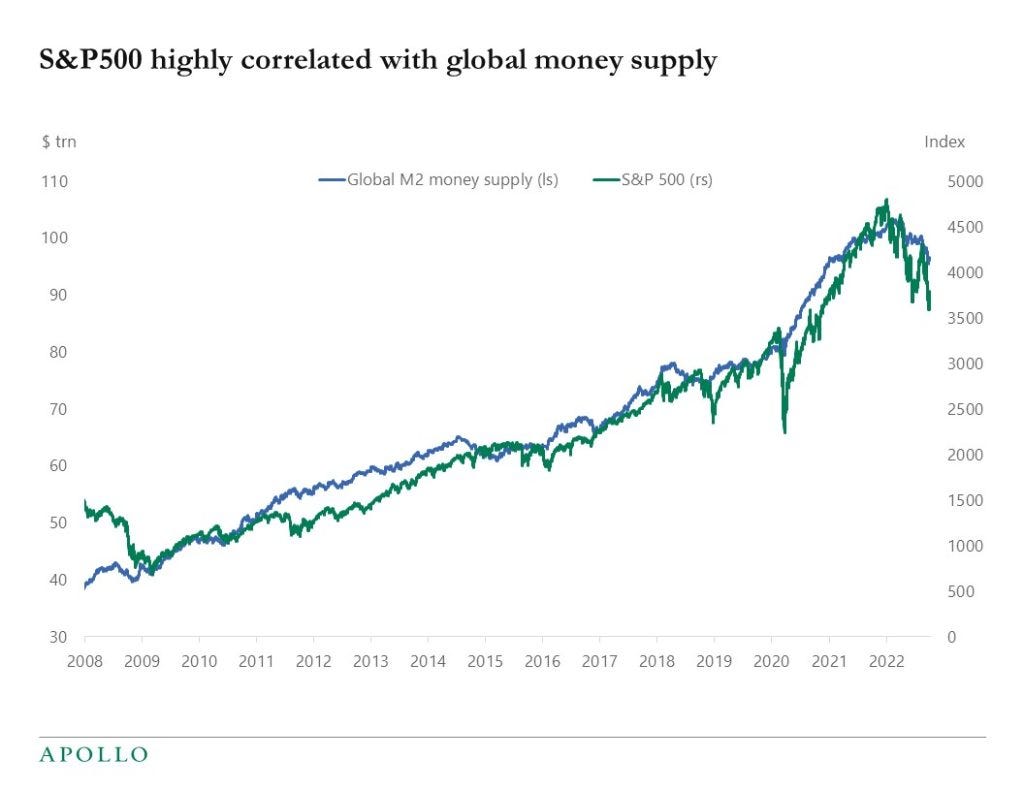

Alas, that simple and closed system is not the world we live in. For various reasons which are beyond the scope of this article, money does not generally retain its value. Through various mechanisms, many of which are opaque and inequitable, the money supply expands significantly over time. It is a simple mathematical fact that the addition of more money into an economy dilutes the purchasing power of existing money, all else being equal. As Milton Friedman famously said, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. The purchasing power of the world’s strongest currencies have declined in the order of 90% over the past 100 years. The dollar has been diluted over 99% over this period, the difference being owed to deflationary efficiencies such as technology and globalisation mentioned in the paragraph above.

In the real world, saving is not a viable option. When the unit you are endeavouring to save is being continuously watered down through the digital creation of new units, you may be able to save in form (the actual number of units) but not in substance (the proportionate claim on goods and services you have earned). This is especially true over any significant period of time, and so everybody must by necessity become an investor merely to stand still. In such a system, keeping your money in a savings account with interest in a fractionally reserved bank is an investment, albeit one that rarely matches the monetary inflation rate. The bank is lending out your money on leverage to earn a return, giving you a cut, and taking a risk to do so. This risk may appear negligible until the term ‘bank run’ reenters the lexicon every other decade.

In this world, people must by necessity invest merely to save and the distinction in terms is lost. People living this reality inherit a warped sense of entitlement that money can and should just ‘grow’, as if they are in fact depositing a sunflower seed with their broker. We rarely stop to question where the growth of this perpetual motion machine originates. It is, for the most part, a debasement chart viewed upside down.

The Investing Status Quo

Because money is losing value, we buy things that we believe other people will need or want to buy in the future. This is why real estate investing has become so popular. Due to various constraints (many of which are artificial), the housing stock increases at a slower rate than the money supply, meaning that housing generally appreciates nominally in price despite being a logically depreciating asset. The perversion of incentives then compounds, and as more people ‘bank on’ these real world assets, governments are compelled to maintain the momentum. As we have outlined in a previous piece, this phenomenon is hugely damaging to society more generally and a reliance on housing as a vehicle to store value is not compatible with the abundant and affordable housing required for human flourishing.

Although we are generalising significantly for the sake of simplicity, it is worth briefly mentioning that all jurisdictions have their own quirks and variations when it comes to investing norms, which can be largely explained by differing laws, culture and tax treatment. While the US and UK have attractive tax-advantaged retirement accounts, Irish ‘investors’ are more restricted by tax rules and generally lean more into property. This article by Michael O’Connor, quoted in part below, is worth reading in full:

“Firstly, the bulk of the Irish retail investment scene is built on a financial broker commission system where unsuspecting customers are shoved into these products by 'financial planners' who receive kickbacks and commissions from these investment companies. You think you're getting free investment advice? Believe me; you're not.

Second, the tax treatment of ETF structures is comical in Ireland, and US ETFs aren't even an investment option. A 41% exit tax and an 8-year deemed disposal rule leaves investors stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Choose an overpriced, underperforming product that locks your money away for multiple years or choose the cheaper, better-performing product and suffer the tax consequences.”

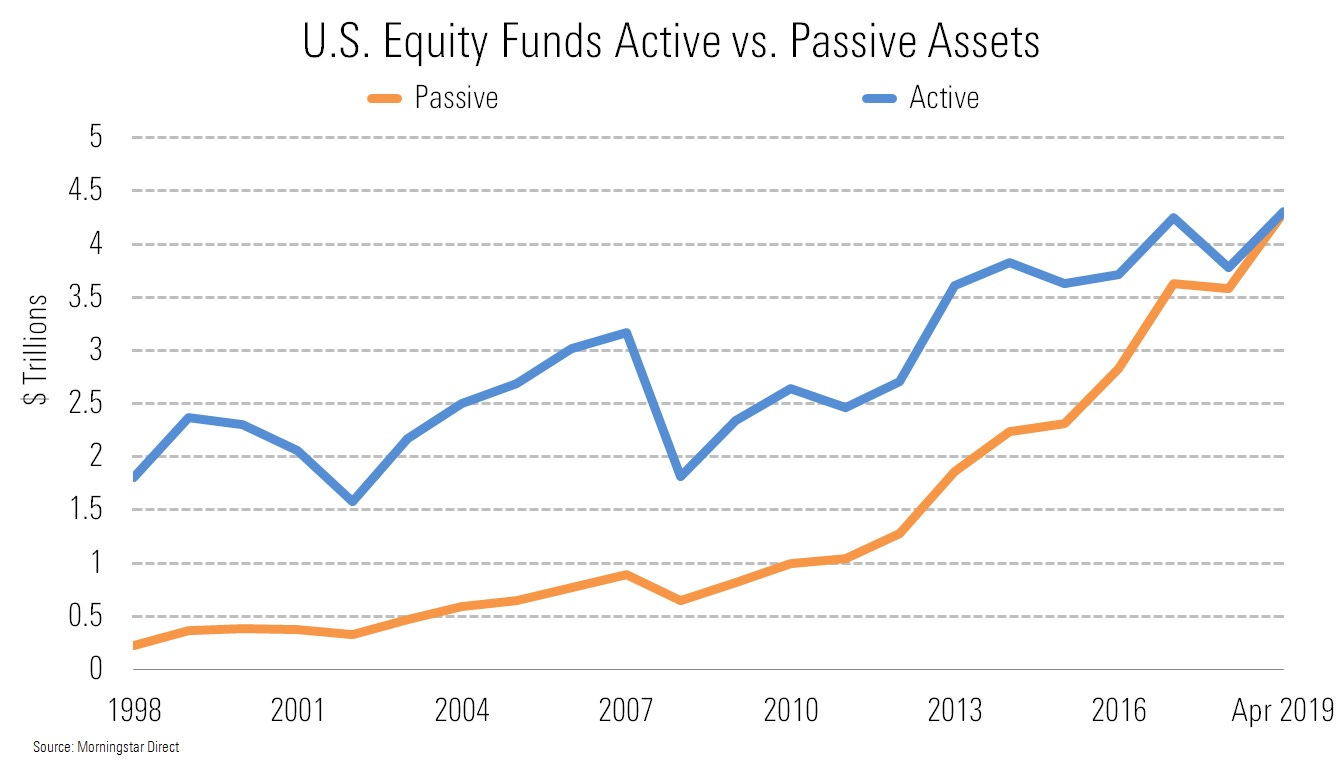

The average person doesn’t have the time, the risk tolerance or the expertise to carefully invest in individual companies or predict the future demand for various commodities, and it would be wasteful if everybody had to do so as a form of second career just in order to save. Over the last few decades, large index funds made up of numerous different companies have been created which allow people to buy diverse shares with ease. It is revealing to note that as recently as the late 90’s, passive investing was dwarfed by active investing; however, it now accounts for a larger share of investment overall.

This is no coincidence, and reflects a growing tendency of people to passively buy index funds as a way of saving under the guise of ‘investing’. Perhaps more surprising is the fact that even professional investors struggle to beat a more passive approach. According to a recent report, over 90% of actively managed funds failed to beat their passive index benchmarks over a 15 year period. Value investing, or carefully allocating economic energy to good businesses, has slowly but surely been displaced by an attitude of throwing mud at the market and watching it go up - a phenomenon largely caused by the debasement of the denominator. This is the form of mindless investing that might be encouraged by those who would begin forming incoherent sentences involving the words “pyramid scheme” and “greater fool” when dismissing Bitcoin. Money, functioning properly as a store of value, can simply be viewed as a call option on all of the goods and services in an economy - the ultimate index fund if we use the investor’s comfortable lens, including everything and excluding nothing. If such a money is global and uncensorable, we remove jurisdictional risk and increase our upside considerably.

Second Order Effects

While the status quo described may at first glance appear to be a harmless way of escaping the effects of an expanding money supply, this is not necessarily the case. First, while it has worked in the US in recent decades, there is no guarantee that this will continue indefinitely, and it almost certainly won’t. The Japanese stock market just recently broke through an all time high after 34 years. Secondly, mindlessly allocating capital to companies tends to favour larger companies which are generally part of indexes like the S&P 500 by virtue of size. This gives such companies a competitive advantage against smaller companies and start-ups. To quote Peter Thiel’s Zero to One:

“New technology tends to come from new ventures - startups. From the Founding Fathers in politics to the Royal Society in science to Fairchild Semiconductor’s “traitorous eight” in business, small groups of people bound together by a sense of mission have changed the world for the better. The easiest explanation for this is negative: it’s hard to develop new things in big organisations, and it’s even harder to do it by yourself. Bureaucratic hierarchies move slowly, and entrenched interests shy away from risk. In the most dysfunctional organisations, signalling that work is being done becomes a better strategy for career advancement than actually doing work…”

Passively allocating capital to larger companies based on liquidity is to the detriment of entrepreneurship in a society, an essential component of free market capitalism. This allocation at any moment in time is a zero sum game. Every dollar Google or Microsoft receive in passive flows by virtue of their size competes for the salary of a software engineer that a startup couldn’t offer. In the longer term, this impacts dynamism in an economy, and is a net negative leading to an unhealthy trickle up effect of capital. Despite the mantra, if people don’t actually have an informed preference for a political candidate or party, they shouldn’t vote. And they certainly shouldn’t pay someone else to cast their vote for the largest party by political funding for the sake of it. Yet, this is precisely what we are incentivised to do for capital allocation.

We have explored why normal people speculate with property and the stock market as a means of saving for their futures. There are other means, including purchasing government and private debt, and commodities such as Gold and Silver. All of these things are subject to their own market risks and are not all correlated, which is why it has become popular to bundle them together as part of a ‘balanced and diversified portfolio’. One part hedges the performance of another, with a general upward trajectory. Recent decades have seen the emergence of the consensus 60:40 portfolio, whereby people are encouraged to hold 60% of their investments in equities which can ‘grow’ in value, and the remaining 40% in liquid government debt which provides security and ‘tends’ to perform better when equities are down. It is notable that this ‘foolproof’ strategy has just had its worst year in decades due to inflation. Most people outsource the headache of dealing with all of this by paying large pension funds and asset managers to hold these portfolios on their behalf, for a fee.

Sample ‘Balanced Portfolio’’: Source Ferguson Wellman: https://www.fergusonwellman.com/investment-strategies-sample-balanced-portfolio

This system may generally appear to work pretty well despite its negative effects, only some of which we touched upon above. However, visible cracks are emerging and to see the wood for the trees it is necessary to zoom out. It is pretty clear that the modern consensus of a diversified portfolio is setting out to achieve one thing: retain the purchasing power of value invested by capturing the debasement of the money in which all of these assets are measured. By any conventional textbook, money has three functions: store of value, unit of account, and medium of exchange. In the modern world, the store of value function has been outsourced to the diversified portfolio, at least for those fortunate enough to live in countries with deep and liquid capital markets and a strong rule of law upon which these contractual links depend.

The Rub

At this point, you may be thinking that perhaps people are comfortable with the status quo, and maybe this ‘system’ will persist. There is a salient point to consider. Since 2009, a form of money has existed that has a credibly fixed supply.This fact fundamentally alters the investing landscape.

As discussed, all financial investing means buying things that you believe others will value more in the future. When people buy Bitcoin, they are expressing the belief that for various reasons, such money will be increasingly valued. Such people are acting rationally. The key message of this article is the following: the competition for value is not enclosed within the system of a fiat currency or fiat currencies more generally, but at a more fundamental level between monies, and Bitcoin is a new form of money. Over recent decades, people have become comfortable being told what money is by the State, so are largely oblivious to the fact that monies can and do compete.

History is littered with examples, but we don’t need to consider the centuries-long struggle between Gold and Silver for primacy to prove this point. Let’s just take modern day Lebanon. The Lebanese Pound has experienced triple digit inflation for three years now. People confronted with this reality have predominantly reacted by hoarding US Dollars, despite official restrictions. Converting their economic energy to money which allows them to escape a decaying system is the best available option, because, even though the stock market and property prices may be rising nominally, decaying money infects the health of the entire system. The violence and pace of this dynamic does not, in our view, render it substantively different to that which is occurring more generally and gradually with Bitcoin.

Forcing Factors

If you are not convinced that change is afoot, this is where a more global perspective and some fundamental game theory enters the equation. While ‘investors’ in the West may be content with the status quo, the majority of the world’s population live in countries without a strong rule of law, enforceable property rights and with persistently high inflation, and they may have another view. In countries with capital controls preventing people escaping monetary inflation, a form of uncensorable money that cannot be debased becomes highly desirable. When this occurs at scale, many of the capital structures supporting our ‘diversified’ Western portfolios begin to unravel. In short, when those most immediately incentivised begin to make the transition, everybody is forced to do so. Liquidity begets liquidity, as we have witnessed with the index funds already discussed.

As the market capitalisation of a neutral form of sound money approaches a currently unknown critical mass, investment vehicles consisting of debt-leveraged Irish and Australian properties will start to look like they are swaying upon a tower of cards. What happens when demographic projections make it clear that our societies will have shrinking populations by the time those currently in their earning prime want to retire? Does the coveted investment property ‘nest egg’ seem quite as appealing then? In advance of this, the social division being directly caused by housing unaffordability may force governments to take decisive action to increase affordability, even if this directly threatens the stability of the financial system. A system that pits the interests of different groups of citizens directly against each other is bound to be highly unstable. It is difficult to imagine rational investors with the ability to contemplate the future being comfortable with the current arrangements.

Without getting drawn into geopolitics, there is an insatiable demand for a neutral settlement and reserve asset. If and when Bitcoin becomes liquid enough to fill this role, the global demand for US treasuries will inevitably recede in earnest. How long will the world be willing to subsidise US defence spending and dominance through the buying of ever expanding US government debt? These broad macro trends are intimately tied to the value of US index funds and debt instruments, and therefore your 401k if you are a US citizen.4 Once it becomes the norm to hedge against this, the writing is clearly on the wall and the exodus accelerates.

This is not intended to be sensational, and the above paragraphs are mere flavours of why the current system will likely not maintain its precarious balance. We haven’t elaborated upon unsustainable national debts, the reemergence of great power competition in a multipolar world, or the increasing use of money as a tool of political enforcement, domestically and internationally. The law of entropy applies, meaning that there are more ways for this system to degrade than strengthen.

A Brutal Game

Why is Bitcoin relevant to other forms of investing? In essence, because it is all one pie of subjective value for claims over real goods and services in an economy, and in the immediate term, it is a zero sum game. Being friends with the biggest bully in the playground is all well and good until another comes along. If any significant portion of the world’s population discovers that there is a store of value that is more liquid, more inflation resistant, more global, more accessible, more divisible, and more appealing than the proxies people currently use to store their monetary value, the result will be brutal for those that are caught off guard holding inferior assets. It will be a form of monetary Darwinism in the digital age.

As it becomes clearer that Bitcoin is a legitimate and indeed superior method of value preservation, all other forms suffer, and this becomes a self-reinforcing feedback loop. For those who may scoff at the idea of legitimacy, the approval and initial performance of Bitcoin ETFs in the US demonstrates that mainstream thinking has changed. When the world’s largest asset manager is calling Bitcoin an “instrument that can store wealth”, it is clear that the narrative has substantially shifted.

“The most dangerous thing is to buy something at the peak of its popularity.”

Price to earnings ratios are high by historical standards. With current debt burdens, sovereign bonds are unlikely to provide sustainable positive real yields. Real estate prices are at all time highs measured in average incomes, such that any further increases risk catastrophic social unrest. These things are true before we consider Bitcoin and its current asymmetric prospect. The total addressable market for storing value is in the hundreds of trillions of dollars. Bitcoin is currently sitting at approximately one.

If Bitcoin continues to monetise exponentially, it draws value from elsewhere. American investors whose retirement plans rely on the value of the S&P 500 will be underwhelmed. Irish workers whose pensions consist of second homes will have their feet taken from under them. Value investors who have bought shares of companies at PE ratios of 25X, may have been right within the system as they understood it, but still dead wrong. While all of these assets will still have some value, this value could be very significantly diminished when stripped of the monetary premium currently attached and repriced in a form of money that doesn’t continually debase over time.

Investing in Better Money

Benjamin Graham said “in the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” Many investors will be familiar with these words. They apply equally to how the market weighs competing forms of money. While Bitcoin may appear to be a speculative asset subject to the volatility caused by short term ‘voting’, any objective assessment of its longer term performance indicates that the market is continually ascribing it a higher value weight against existing currencies. Since Gold’s failure, fiat currencies as a collective have represented a quasi-closed system. They could only be measured from each other’s imperfect and ever-debasing vantage points, and the world became used to assessing value through the least bad option, which for some time now has been the US dollar.

Since 2009, this is no longer the case, and a chasm has been opened to reveal a superior system. This article won’t endeavour to explain why this is; however, there are plenty of excellent resources which do so. Thus far, the violence with which the repricing has occurred has caused many to dismiss it. Others are attempting to understand this as just another mechanism within the system they are familiar with. Failing to recognise that this new system is also competing for value, albeit in a more fundamental and primal way, may be a costly mistake.

“To survive, everyone must convert their work into assets that are scarce, desirable, portable, durable and maintainable…… The entire world, for the last 5,000 years, has lived on analog assets: real estate, gold, silver, paper money, bonds, buildings, collectibles, sports teams, livestock, cattle, bales of tobacco, seashells and glass beads. Now we have a digital asset.” 5

Over recent decades, the concepts of investing and saving have become muddled in the collective mind. As a result of an accounting system that constantly leaks economic energy, we have become accustomed to formulaically buying things that others will need in the future in order to preserve purchasing power. This will not change because those of us making this case will successfully convince people that it is an inefficient and pernicious way of storing value which causes harmful real world distortions. Rather, now that this function can be outsourced more successfully to an abstract and thermodynamically sealed accounting system, the appeal of doing so will recede and the status quo will begin to fail as the world is repriced in sound money. This outcome requires nothing more than people acting in their own self interest.

Bitcoin is still young and faces various risks that we will not delve into here. It is understandable that its volatility is off-putting to many who are seeking a conservative store of value; however, overcoming this requires one to understand and accept that the monetisation of a new currency from scratch could hardly be otherwise, and the ability to extrapolate that continued adoption will lead to greater stability over time. For this reason, at this point in time, Bitcoin can properly be considered an investment. It is not a traditional ‘asset’ with cash flows or dividends. It is simply a better system for storing and transferring value itself which cannot be debased. Its success will usher in a world in which saving is the norm and investing is reserved for willing investors. It appears to us that there is immense productivity, social benefit and yes, value - whatever that means - in that.

Under a fixed supply money, the prices of various goods and services would still fluctuate against others and the currency due to factors such as the changing of subjective consumer preferences, demographics, supply chain disruptions, and varying efficiency gains in different areas. While it is complex, it is logically the case that lower overall prices would be a clear indicator of economic progress and an improved standard of living.

There are many deep rabbit holes one could venture down at this point concerning the stance we have taken here. Some believe that those unwilling to ‘make their money work’ or take risk deserve to pay a form of tax for leaving it idle, and that having the perpetual incentive to invest allows for the funding of projects that would not otherwise be funded. The normative stance, or what is the best way for capital allocation to function, is theoretical and irrelevant when people face the rational choice of which money to use; however, for the record, we believe those arguments to be completely without merit.

This is of course a simplification, because more sophisticated investors understand the importance of matching or surpassing price inflation as measured by the consumer price index, and the opportunity cost of the perceived ‘risk free rate’ of the US Treasury bond; however, it is a simplification that is worth drawing upon for its explanatory power, and because most people are not ‘more sophisticated investors’. It is also worth highlighting that these benchmarks are almost always below the rate of monetary inflation, which is far less understood and has been well masked by the deflationary forces of globalisation and technological advances in more recent decades. Put simply, all else being equal almost everything should have gotten cheaper over time, though most things have not. In effect, this means that many who have assumed they have been winning, have been losing in real terms.

This is by no means a simple concept. In essence, a reduced global demand for treasury bills and dollars would cause interest rates to rise dramatically, devaluing existing bond and currency holders. Alternatively, if the Federal Reserve was to step in as a buyer, this would significantly devalue the dollar and lead to significant inflation, hurting US investors in real terms in either event.

Michael Saylor, Madeira, 01 March 2024